Watermelon Man (1970)

White salesman Jeff Gerber (Godfrey Cambridge) wakes up to discover he’s become a black man overnight. His transformation causes problems at work, with the police, and with his neighbors. His seemingly liberal wife (Estelle Parsons) who once chastised him for not caring about the problems faced by black people in America, leaves him because she can’t handle the stress.

The movie ends with Gerber joining a black militant group he once disparaged.

Directed by Melvin Van Peebles, this biting social commentary is no less relevant fifty years later. Amazingly, Peebles fought the studio to hire a black actor to play the lead. Godfrey Cambridge was a comedian and peer of Bill Cosby, Dick Gregory and Nipsey Russell. He died in 1976 and is now mostly forgotten in the pop culture landscape, but he’s excellent here.

Peebles also battled writer Herman Raucher who wanted the film to end with Gerber waking up to discover the whole experience had been a dream. Raucher saw the film as a satire of white America’s attitudes about race, Van Peebles saw it as an affirmation of the black power movement.

This film launched Van Peebles as a major director; but he turned down lucrative studio offers to forge his own path as a seminal figure in independent film. This film remains a stirring testament to his unflinching vision and honest rawness.

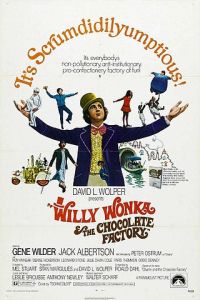

Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971)

Famed chocolatier Willy Wonka (Gene Wilder) announces he has surreptitiously placed five golden tickets in his Wonka Bars and the recipients of these tickets will be allowed an exclusive tour of his mysterious factory.

After weeks of speculation, the winners are announced: Augustus Gloop, Violet Beuregard, Mike Teevee, Veruca Salt, and Charlie Bucket, an assuming boy who lives a quiet life with his widowed mother and four bedridden grandparents.

Wonka’s chief rival, Mr. Slugworth, promises each of the winners a healthy reward if they bring back a sample of Wonka’s latest invention, the Everlasting Gobstopper.

Upon entering the factory, the children discover it’s run by orange-colored Oompa-Loompas, who supply Wonka with cheap labor.

During the tour, the children fail to follow Mr. Wonka’s clear instructions and each meets a disastrous fate. Augustus is sucked into a pipe, Mike is shrunk, Vercua falls down a garbage chute, and Violet inflates into a giant blueberry. Only Charlie remains unharmed at the end of the tour.

Wonka reprimands Charlie for stealing some Fizzy Lifting Drinks, but after a chastened Charlie returns the Everlasting Gobstopper, a delighted Wonka informs him the entire enterprise was a test to find a successor. By refusing to align with Slugworth, Charlie passed and will inherit the factory.

Despite Roald Dahl’s disappointment with this adaptation of his book, it’s a fantastic approximation of his worldview and aesthetic, dangerous and scary but encapsulated in childhood wonder.

Thinking about the Golden Ticket, Charlie and Grandpa Joe floating to the ceiling, Violet, Veruca, and the Oompa Loompas brings a smile to my face.

An icon of a Generation X childhood, parts of the film feel dated, but it’s vastly superior to the unfortunate remake.

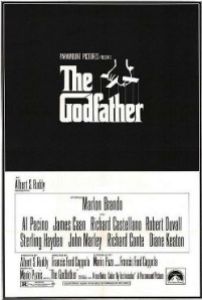

The Godfather (1972)

Despite pressure from the other mafia families to enter the drug smuggling business, Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando) steadfastly refuses. In retaliation, the other dons kill his most trusted associate, Luca Brassi, and convince one of his capos, Tossi (Abe Vigoda) to betray the family.

After Vito’s son Sonny (James Caan) is killed in an ambush, he sends his oldest son Michael (Al Pacino) to Italy for protection, but when Michael’s Italian wife is killed in a car bomb, he returns home to the join the family business. Becoming the new don after Vito’s death, Michael’s first order is the execution of Tossi and the dons of the five families

Francis Ford Coppola elevated Puzo’s popular, middlebrow novel into a sublime commentary on American capitalism and love of violence.

There’s so much to love: the horse head, Robert Duvall as consigliere Tom Hagen, Abe Vigoda.

I’m sure the actual mafia is more Goodfellas (1990) and Bugsy (1991), but when I think of the mob, I see a mumbling Brando lurking in the shadows.

Much like the mobster succeeded the western outlaw in the beginning of the 20th century; the mobster movie succeeded the western in the late 1960s, and with this film, the cowboys of John Ford finally gave way to the mobsters of Martin Scorsese.

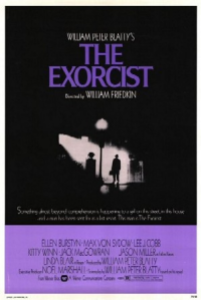

The Exorcist (1973)

Disturbed by several mysterious deaths, Cris McNeil (Ellen Burstyn) slowly realizes her daughter, Regan (Linda Blair) is possessed by a demon and asks father Damien Karras (Jason Miller) to perform an exorcism. Undergoing his own crisis of faith, Karras calls experienced priest Lankester Merrin (Max von Sydow) to help.

After Merrin is killed by the demon, Pazuzu (Mercedes McCambridge), Karras convinces it to enter him and throws himself out a window, sacrificing his life to defeat the evil monster.

Despite its reputation, this is not a horror film, but a deeply spiritual film, one of the most honest fictional representations of the problem of evil and the sacrifices of faith.

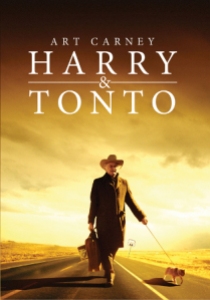

Harry and Tonto (1974)

Widower Harry Combes (Art Carney) moves in with his son after his building is condemned, but grows restless and begins a cross-country trip with his pet cat Toto.

On the road, he befriends a Bible loving hitchhiker, a runaway, a prostitute, and a traveling health-food salesman. He visits his daughter, Shirley Mallard (Ellen Burstyn) in Chicago and an old flame, Jessie Stone (Geraldine Fitzgerald) who suffers from dementia.

He spends a night in a Las Vegas jail with Sam Two Feathers (Chief Dan George) before arriving in Los Angeles, the home of his youngest son Eddie (Larry Hagman).

I’m a sucker for any film about the elderly reflecting on their life, and Art Carney is amazing in this small movie with quiet ambition.

If you’re interested in seeing who beat Pacino in The Godfather Part II for Best Actor, or if you love movies focused on people coming to terms with their mortality, this movie is for you.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975)

After prisoner Randle McMurphy (Jack Nicholson) arranges a transfer to a mental institution in an attempt to avoid hard labor, he challenges the ward’s sadistic nurse Mildred Ratched (Louise Fletcher) at every turn, and befriends “Chief” Bromden, a Native American who pretends to be deaf and dumb. After Ratched forces him to undergo electroconvulsive therapy, McMurphy plans his escape.

He throws a farewell party, but falls asleep before he can leave. The next morning, a vengeful Ratched bullies one of the patients into suicide. Enraged, McMurphy attacks her before he’s hauled away by security.

When McMurphy returns to the ward several days later, Chief notices scars on his forehead indicating he was lobotomized and smothers him before breaking out of the ward himself.

Jack Nicholson’s coming out party is firmly entrenched in the American pantheon. Every time I watch, I’m pleasantly surprised to see Danny DeVito and Christopher Lloyd as patients at the mental institution and blown away Louise Fletcher didn’t make a career playing a cold-hearted bitch.

While Ken Kesey’s novel makes it clear, the film obscures the reason for McMurphy’s prison sentence: statutory rape of a 15-year-old. As a result, the film is a much more palatable indictment of contemporary mental health treatment.

Amazingly, Milos Forman is a two-time Academy Award winner for Best Director, yet most Americans have never heard his name.

Network (1976)

After learning he’s been fired as anchor of the UBS Evening News, Howard Beale (Peter Finch) stuns his audience by announcing he’ll commit suicide on air during next Tuesday’s program.

Beale pledges to offer an apology the next evening, but instead launches into a tirade about the current state of America, declaring he’s “mad as hell and not gonna take it anymore.”

His unrestrained anger is a hit and the show rises to the top, but when he turns his indignation towards the network and a proposed merger with a Saudi conglomerate, he’s confronted by company chairman Arthur Jensen (Ned Beatty). The charismatic, delusional Jensen convinces Beale to soften his approach.

However the kinder, gentler Beale’s ratings plummet and, to boost the network, executive Diana Christensen (Faye Dunaway) and her boss Frank Hackett (Robert Duvall) make a deal with terrorists to assassinate Beale on air.

This movie about network politics in the 1970s, ponders the role of ethics and morality in contemporary capitalism.

It’s a shame Rocky beat it out for Best Picture but it’s an understandable debate. However, Beatrice Straight should never have beaten Jodie Foster in the race for Best Supporting Actress. She was in the movie for less than six minutes while Foster’s star-making role has more than withstood the test of time.

Sidney Lumet’s a great director, but the credit for this film belongs to writer Paddy Chayefsky who brilliantly foreshadows Rush Limbaugh, Keith Olbermann, Bill O’Reilly, and Rachel Maddow. Anger makes for great television.

Oh, God! (1977)

When supermarket assistant manager Jerry Landers (John Denver) is picked by God (George Burns) to be his emissary, he encounters resistance from his wife (Terri Garr), children, bosses, skeptical media outlets, and jealous religious leaders. Sued for defaming a well-known pastor, he’s forced to call the one witness who can corroborate his story: The Almighty.

Denver is adequate, but not spectacular, but George Burns was born to play a mischievous old man and the supporting cast, including Garr, Donald Pleasance, Ralph Bellamy, Williams Daniels, and Paul Sorvino, are excellent.

The film takes a progressive stance on the difference between the world’s major religions: “Jesus is my son, Buddha is my son, Mohammad is my son,” but mostly avoids specific theological issues. Placing the blame for humanity’s problems and foibles on human beings, it encourages us to see love as the solution, echoing the message of Christ.

Director and avowed atheist Carl Reiner says,”I have a very different take on who God is. Man invented God because he needed him. God is us.” This explains what the film was trying to do: demystify and humanize God. Reiner may be an atheist, but his film is one of the best and loveliest films about a heavenly father.

The End (1978)

When Sonny Lawson (Burt Reynolds) learns he’s dying from a rare blood disease, he decides to commit suicide rather than spend his remaining days in excruciating pain.

Preparing for his death, he visits his ex-wife Jessie (Joanne Woodward), daughter Julie (Kristy McNichol), girlfriend Mary Ellen (Sally Field), and his parents, Maureen (Myrna Loy) and Ben (Pat O’Brien).

After his first suicide attempt fails, he wakes up in a psychiatric hospital. Fellow patient, Marlon Borunki (Dom Deluise) agrees to help Sonny kill himself, but the two men prove extremely inept. After several additional failed attempts at taking his own life, Sonny desperately swims into the ocean to drown, but, motivated by love of his daughter, he abandons the effort, only to be met on shore by a murderous Marlon.

Burt Reynolds directed himself in this witheringly funny film which feels like a spiritual sequel to Hal Ashby’s Harold and Maude (1971). Reynolds never pulls back from the laugh, no matter how uncomfortable the scene becomes.

The scene where Sonny confesses to a young, inexperienced priest, is a brilliant deconstruction of religion. The scenes with Reynolds and Field explode with sexual chemistry. Joanne Woodward is great as Sonny’s shrill ex-wife and it’s satisfying to see old school stars Myrna Loy and Pat O’Brien getting a nice send off.

The highlight is Dom Deluise indelible manic performance; the scene when Marlon and Sonny meet is terrifyingly funny.

Few directors would have signed on for a farce about suicide. Most would have softened the subject and it would have wound up turning to sentimental mush like The Bucket List (2007). Reynolds’s ability to make this film on his terms speaks to how much power he had in the late 1970s.

The Tin Drum (1979)

Just before World War II, three-year old Oscar Matzerath decided to stop growing.

Despite his increase in age, he remained, by all outward appearances, a child. This is how he experienced Nazism, concentration camps, the Soviets, and the American liberators.

This movie is about children forced to make adult decisions because of circumstances beyond their control. Because the main character doesn’t age, we’re forced to filter the film through the eyes of a child, and see how absurd many of the most pressing twentieth century calamities actually were.

An anti-war film is one thing, but an anti-war comedy is more effective.

Volker Schlöndorff’s adaptation of Günter Grass’s 1959 novel is an audacious, surrealist film, like Salvador Dali directing MASH.