Dreams (1990)

Nearing the end of his life, legendary director Akira Kurosawa reflects on his childhood and finds inspiration for several beautiful vignettes.

After a child stumbles upon a fox wedding during a sunshower, his furious mother demands he apologize.

Their surviving commander orders the ghosts of Japanese soldiers returning from the second World War come to terms with their demise, while he struggles with his own culpability.

Vincent Van Gogh (Martin Scorcese) travels though his paintings and expounds on the philosophical and aesthetic reasons behind them.

In two different segments Kurosawa touches on the anxiety of the nuclear age, particularly in Japan where the first atomic bomb was detonated.

The film closes with a beautiful rumination on the advantages / disadvantages of modernity.

Kurosawa unleashes his fertile mind in this whimsical, lyrical, magical fable: a fitting capper to the career of one of the titans of twentieth century cinema, who exposed the western world to many eastern ideas, including samurai and Japanese moral codes.

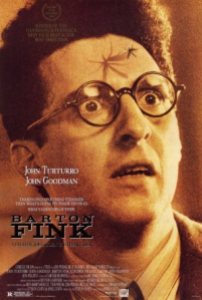

Barton Fink (1991)

Barton Fink (John Turturro) is a celebrated Broadway playwright hired to write Hollywood scripts in the early 1940s. While in California, he stays at the rundown Hotel Earle to maintain his connection with “the common man,” where he meets Charlie (John Goodman), an insurance salesman hiding a dangerous past. Fink dreams of creating important, artistic films, but his boss at Capitol Studios, Jack Lipnick (Michael Lerner), is only interested in making money.

Few actors can boast of working with the Coens, Spike Lee, Adam Sandler, and Michael Bay; John Turturro has been in multiple projects with each of them. He’s an incredible versatile performer and very good as Barton, but this movie belongs to John Goodman’s Charlie. The Coens always bring out the best in him in films such as Raising Arizona (1987), The Big Lebowski (1998), and O Brother Where Art Thou (2000), but this, easily his darkest and most fearless work, is in a different league and leaves an indelible impression.

John Polito (an early Coen favorite), Steve Buscemi, John Mahoney, Tony Shalhoub, and Judy Davis round out the supporting cast.

In the past decade, the Coen brothers have worked to make their films more accessible and mainstream, but this film remains one of their most challenging; the last third of the movie descends into a dream-like Lynchian madness involving a serial killer, a huge fire, a severed head, and a postcard.

Nonetheless, this was immediately recognized as an important film and helped separate the brothers from the glut of quirky, independent filmmakers at the end of the twentieth century. At the 1991 Cannes Film Festival, this under appreciated and misunderstood film became the first to win the Best Picture, Best Actor, and Best Director awards at the festival.

It’s a funny, insightful parody of the Hollywood studio system at the beginning of World War II and a probing look at the nature of art. Fink is dismayed when he’s assigned to write a film about wrestling because he considers the subject beneath him, but four hundred years ago, Shakespeare’s plays were disdained as low culture entertainment; now, they’re the pinnacle of Western civilization. In five hundred years, will critics be studying the collected works of John Cheever or Full House?

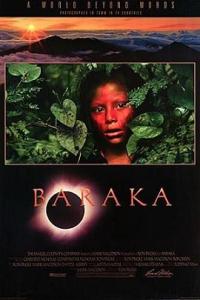

Baraka (1992)

This spiritual successor to Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisquati (1982) was directed by Ron Fricke, the cinematographer of the earlier film.

Containing no narrative, it’s a series of long tracking shots of people and places from around the world, often using time-lapse photography: the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, oil fields in Kuwait, Auschwitz, African tribal ceremonies, a crowded subway terminal. It’s National Geographic without interpretive voice overs.

A statement about the interconnectedness of humanity, it’s a breathtaking, beautiful film highlighting the diversity of the world and the wonder of creation.

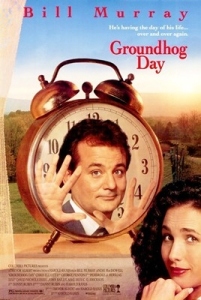

Groundhog Day (1993)

When Pittsburgh weatherman Phil Connors is assigned to cover the Groundhog Day festival in Punxsutawney, he’s inexplicably forced to relive the same day over and over again.

As Ned Ryerson, Stephen Toblowsky straddles the line between annoying, over-eager salesman and pathetic everyman; Andie MacDowell’s Rita is the most genuine person in the film and its emotional anchor; Chris Elliot’s physical comedy serves as a counterbalance to the film’s cerebral aspirations, but this movie belongs to William James Murray.

Prior to this, everyone knew Bill Murray was funny, but no one knew if he could act. As Phil Connors, he runs the gamut from depressed loser to jaded cynic to self-centered asshole to altruistic boy scout. Caddyshack (1980) and Ghostbusters (1985) made him a star, Groundhog Day made him an actor.

This movie breaks countless storytelling rules, but no one walks away thinking about the gaping plot holes. Instead, viewers fill in the blanks with their own metaphysical and philosophical explanations, whether they be Buddhist, Christians, humanist, or conservative.

Director Harold Ramis is often compared to fellow Chicagoan John Hughes, another hugely influential comedic voices in the late twentieth century. I prefer Ramis, but the difference between the two is negligible.

From Ferris Bueller, to Del Griffith, to Kevin McCallister, Hughes’s films feature insecure people trying to figure out how the world works.

From Ty Webb, to Peter Venckman to Phil Connors, Ramis’s films feature overly secure people trying to understand why the world doesn’t work the way they think it should.

On paper, this philosophical, romantic comedy about existential angst with an underdeveloped fantasy plot shouldn’t rank as one of the greatest films of all time, but it does.

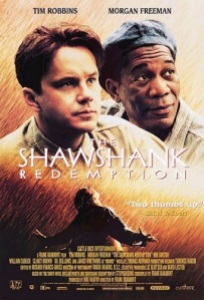

The Shawshank Redemption (1994)

1994 was a miracle year for movies, but while Forrest Gump was a technical marvel and transformed Tom Hanks into a national treasure and Pulp Fiction ushered in a new era of hyper violence, the cream of the crop was the story of the wrongfully convicted Andy Dufresne.

Its continuing power is due to the amazing cast of characters.

Thousands of people dream of Morgan Freeman narrating their lifestory, but what they really want is the comforting, soothing gravitas of prisoner Ellis “Red” Redding magnifying the minutiae of their lives.

Bob Gunton is one of the greatest screen villains as the hypocritical, Bible-thumping, slightly obtuse warden, Samuel Norton.

James Whitmore is heartbreaking as Brooks Hatlen, the lifelong prisoner unable to adjust to life on the outside.

Andy’s quiet quest to secure his freedom stands in contrast to the bitterness and defiant anger we expect, and the image of him emerging from the sewer a free man and looking up into the falling rain is a triumph of the human spirit.

Before Sunrise (1995)

Jesse (Ethan Hawke) is a young American who just ended a long-term relationship with his girlfriend and took a trip through Europe to “find” himself.

Celine (Julie Delpy) is young European returning to university in Paris after visiting her sick grandmother.

The pair meet on the train to Vienna and walk around the city over the course of one evening. What begins as innocent flirtation becomes a symbiotic relationship built on self-discovery. Without the baggage of their pre-existing identities or the burden of a relationship existing beyond this one night, Jesse and Celine don’t have to guard themselves. They can be vulnerable, safe in the knowledge this vulnerability will vanish twelve hours later, when Jesse boards his plane to the United States.

Complications arise when they find themselves drawn to the raw intimacy they’ve created with one another. Despite their limited time together, the closeness they forge is genuine. The movie ends with their parting, but the promise of a future meeting is inevitable, and while this film does not reveal if it is a promise kept, everyone watching the film assumes it must be.

In this film, Richard Linklater creates one of the most fully realized romantic pairings of the late twentieth century. It’s idealized and, in many ways, more fantasy than reality, but it’s a fantasy we want to believe is true.

Twenty years (and two sequels) later, Celine and Jesse remain one of the most vital onscreen relationships. Theirs is the stuff of fairytales, only in this version we see what lies beyond happier ever after and learn, despite the confusion and pain, it’s even more beautiful than we imagined.

The Crucible (1996)

In this film inspired by the infamous Salem Witch Trials, John Proctor (Daniel Day-Lewis) love his wife Elizabeth (Joan Allen), but an earlier infidelity with Abigail Williams (Winona Ryder) causes a rift in their relationship which ends in violence and engulfs the whole town.

Daniel Day-Lewis rarely disappoints. His John Proctor is torn between protecting his reputation or his family. Ultimately, he chooses his family, but like The Gift of the Magi, his wife refuses to confirm his unfaithfulness.

Beginning in the mid 1990s, Joan Allen began an impressive decade long run of quality films including Nixon (1995), The Ice Storm (1997), Pleasantville (1998), The Contender (2001), and The Notebook (2004). She brings a quiet dignity to Elizabeth Proctor, who continues to love her husband despite his infidelity.

Winona Ryder is a versatile performer who can be goofy, sarcastic and mean, or quietly manipulative. Sadly, her career was derailed after her arrest for shoplifting. Since then, she’s been relegated to supporting roles in films like Star Trek (2009) and Black Swan (2010).

She’s still relatively young, but I fear we’re going to look back on her career and see it as a squandered opportunity.

Paul Scofield focused on the theater, but the few films he participated in were memorable including A Man for All Seasons (1966), Henry V (1989), and Quiz Show (1994). He’s excellent as Judge Thomas Danforth, the architect of the trials.

Jeffrey Jones who played Thomas Putnam is fondly remembered as the dad in Beetlejuice (1988) and the principal in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986), but those fond memories were tainted when he was arrested for child pornography in 2003.

I’d read Arthur Miller’s play in high school, so I knew the film used the witch trials as an allegory for McCarthyism, but I didn’t anticipate the film’s message about love and commitment which makes it a perfect companion piece to The Age of Innocence (1993), also starring Day-Lewis and Ryder. The earlier film shows what sacrifices must be made to maintain fidelity in a relationship, while this film shows the consequences of breaking this vow.

Wilde (1997)

Convicted of gross indecency (homosexuality), famed author Oscar Wilde was imprisoned for two years at the height of his fame. His friends mostly abandoned him in the face of the controversy, although his wife remained married to him for her children’s sake.

While in prison he wrote De Profundis, a letter to his former lover, Bosie (Jude Law) whose father, the Marquess of Queensbury (Tom Wilkinson) was responsible for his imprisonment. De Profundis is a moving rumination on the nature of art and existence, as Wilde desperately tries to make sense of his suffering and finds solace in Christ’s example.

Stephen Fry is perfectly cast as Wilde. Jude Law is great as Bosie. Tom Wilkinson is deliciously evil.

As we debate the status of LGBT rights and the limits to what we should accommodate, it’s amazing to consider Wilde, one of the most celebrated writers in the history of the English language was imprisoned for being gay. In 2017, over one hundred years after his unjust imprisonment, he was pardoned.

After Life (1998)

Everyone who dies goes to a station between life and eternity where they must choose one memory from their life to take with them into the next. If anyone refuses, they must work at the station aiding others until they do. One of the current workers, Takashi Mochizuki (Arata), recognizes the latest gentleman he’s assigned to guide, Ichiro Watanabe.

After Mochizuki died during World War II, his fiancée entered into a loveless marriage with Watanabe. As both men help each other come to terms with what their lives were and what they weren’t, Mochizuki discovers his beloved had chosen a memory with him as her eternity, and chooses this moment of epiphany as his forever moment, finally leaving his work at the station behind for the next phase of existence.

I’m a huge fan of films which deal with loss and mortality. Director Hirokazu Kore-eda has created a moving ode to the human experience, which manages to be spiritually satisfying without preaching.

Between this and Departures (2008), I’m beginning to understand the Japanese have a view of death I find immensely satisfying.

I will think of this film often and, prompted by its message, I’m already combing through my memories to determine which ones might make the cut in my own Valhalla.

Magnolia (1999)

The lives of the characters in this film intertwine in a ridiculous labyrinth.

Phillip Baker Hall, perhaps best known as Lt. Bookman in an episode of Seinfeld, is Jimmy Gator, an aging, alcoholic host of a children’s quiz show who, because of his alcoholism, can’t remember if he sexually abused his daughter.

The underrated John C. Reilly is Jim Kurring, a dimwitted policeman in love with Gator’s daughter.

William H. Macy is Donnie, a former quiz show champion who believes dental work will solve his insecurities. After Fargo (1996), it seemed Macy was destined to become a major star, but he seems content with smaller character work.

Jason Robards is Earl Partridge, who wants to reconcile with his son before he dies. Robard’s death one year after the film’s release adds an urgent poignancy to his performance.

Julianne Moore is Linda Partridge, the morphine-addicted, much younger wife of Earl. In my opinion, Moore’s an overrated actress, but she’s compelling here.

Phillip Seymour Hoffman is Phil Parma, a hospice nurse who takes care of Earl.

Tom Cruise plays against type as Earl’s son, the misogynist / pick up artist Frank Mackey, whose fractured relationship with his father manifests in unexpected ways. His performance is a career highlight.

Just as we realize it will take a miracle to unravel the film’s ridiculous plot, the miracle happens: a storm carrying thousands of frogs descends on the city.

Near the end of the film, a succession of characters sing “Wise Up” by Aimee Mann. It’s an odd, haunting scene, forcing us to remove ourselves from the story and focus on the characters.

Director and screenwriter Paul Thomas Anderson understands films in a way few in Hollywood do: the details of the plot of a movie will be forgotten, but great characters such as Jack Horner, Daniel Plainview, and Lancaster Dodd will survive